Self-Scrutiny as Subject

Text by Ivan Rod

Linda, short form of Belinda (English) or Rosalinda (German). No known meaning. The name came to Denmark with the first wave of English names in the latter half of the 1900s. The name is most common in Copenhagen and Zealand and has become increasingly less widespread since the 1980s.

( The Big Name Book , Aschehoug Publishing)

Hansen - patronymic of the male name Hans. Hans is the German short form of Johannes, the most popular male name throughout most of the Christian world during the Middle Ages. The name Hans came to Denmark with the mass German immigration of the late Middle Ages, and has been one of the most common names since. Which is why since 1856 - when the Danish central administration made surnames mandatory - it has been so common. The name Hansen has, however, become less widespread since the 1980s.

(Georg Soendergaard's Danish Surnames , Lademann's Press)

I

It's must be three years ago that the Danish photographer Linda Hansen first told me about her idea. She wanted to find and take portraits of people in Denmark with whom she shared a peripheral common destiny. Women with the name Linda Hansen. Nothing more, nothing less. Not necessarily all the Linda Hansens in the country, but enough to give a representative picture.

I was immediately taken by the idea. Was rapidly, like Linda herself, fascinated by the concept of a series of very different women with one thing in common - the name Linda Hansen.

I'd often thought about what it is that holds people together. Why it is that so many distance themselves from the common destiny a family represents, for example, to surround themselves exclusively by those they choose themselves. It is precisely the common destiny we can't choose that is a mirror image of ourselves. For better and for worse. Either in family relationships or - if you believe in astrology - in relationship to people born at the same time. But this is also what makes it frightening. Yet the mirror image is an inescapable part of our identity. Which is what makes rejecting it problematic.

I couldn't imagine that the women Linda Hansen wanted to photograph would have anything other than their name in common. Any true common destiny would be impossible to find. Or would it?

She told me that the idea had arisen several weeks earlier when she was participating in a photography exhibition in a gentrified area north of Copenhagen. During the exhibition opening a curator had said: 'Linda Hansen ...! How on earth are you going to make it with that name?' At the time she didn't reply. She'd never really thought about her name, and regarded the comment as more tactless than provocative. But it wouldn't go away. Because it was so narrow-minded. It was the prejudice behind the comment that generated the idea. She would find and photograph people called Hansen.

Back in Copenhagen she looked the name Hansen up in the telephone directory, coincidentally under Linda Hansen. There was half a column. Just of Linda Hansens. In Copenhagen alone. Of course - they were the ones she should shoot. The ones with whom she shared a coincidental 'common destiny'. And - as she believed at the time - out of sheer curiosity. But in reality also to defend this section of the Danish population - and thereby herself - against attacks of prejudice.

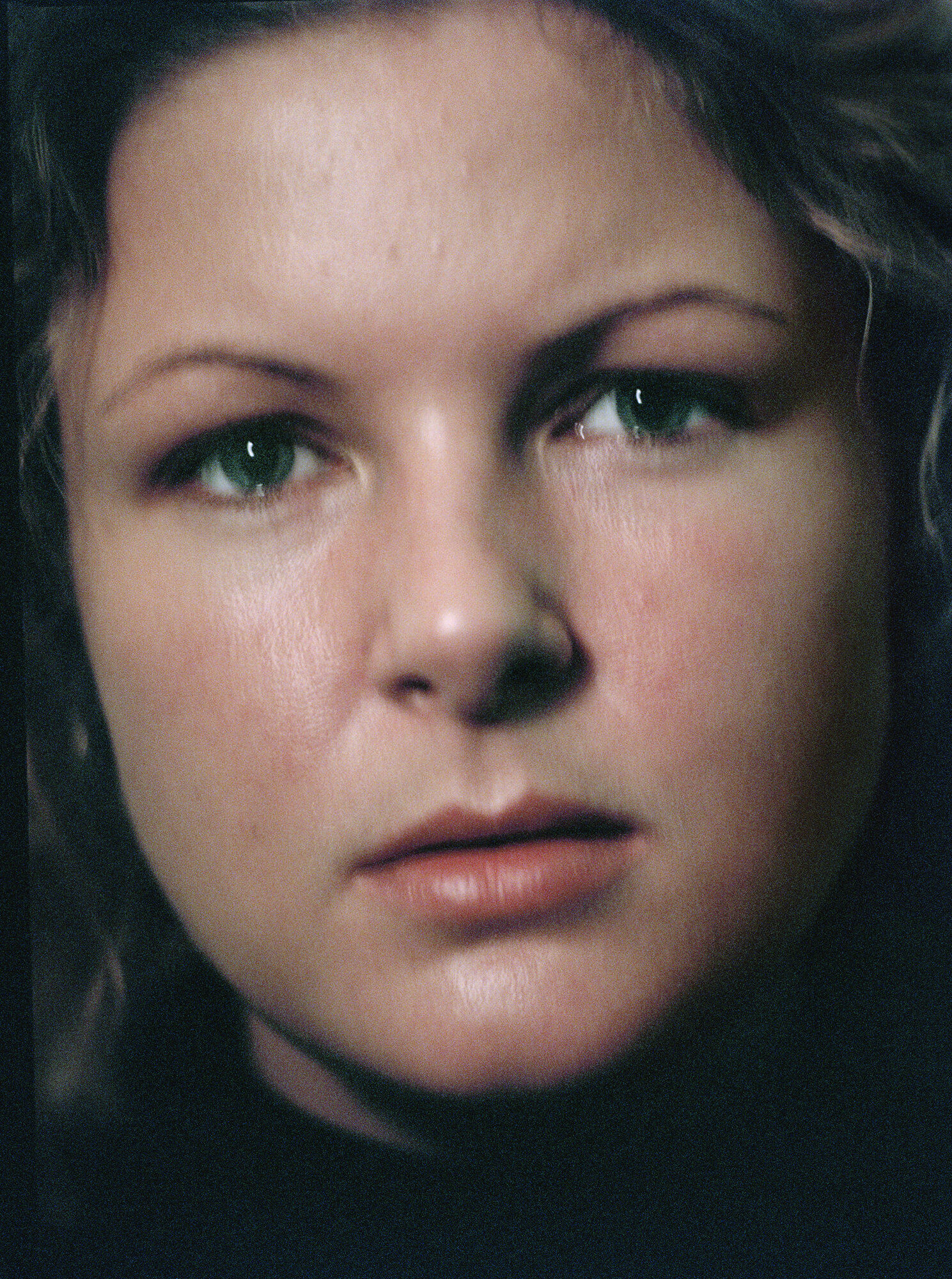

A few days later she met her former teacher from the art photography school Fatamorgana in Copenhagen. She told him about the idea and his response was: 'Linda Hansen? You'll find her in the working classes'. The comment hit home. Maybe because she was a daughter of the working class herself. Her father was a motor mechanic, and her mother a home help. Maybe because the comment was not only obviously provocative and prejudiced, but perhaps precisely because it had an element of truth. About her. And maybe about the others? Taking portraits of her namesakes was to develop into a constant unconscious battle between the acceptance of her own class identity and her rejection of it. And a painful confrontation with her own prejudices. In the end the portraits were to become mirror images of herself rather than representations of her namesakes. Vulnerable self-portraits with self-scrutiny as their subject.

II

According to Statistics Denmark more than 250,000 Danes have the surname Hansen. And more than 10,000 have the first name Linda. The figures made her think of generic labelling - and reminded her of the curator's comment. But when she discovered that only 530 Danes are called both Linda and Hansen - and that the vast majority of them also had one or more middle names - she relaxed a little.

Excited and curious she began the hunt for 'pure' Linda Hansens. She rang and explained what she wanted to do then paid them a visit.

They all got the idea. It was as if all of them, independently of each other, had felt common because of their name. And as if the photographer's interest gave them a chance - in spite of everything - to be written into history. For some it was the first time in their lives they had been proud of their name. And it frightened her that their identities and personalities could be so strongly linked to their name.

She got her own name by coincidence. When she was born her five-year-old brother was allowed to choose her name. He'd seen a film where there was a lovely little girl called Linda, so that was what she was to be called. He'd given her the name because he thought she was something special. An opinion that was subsequently incorporated into her own self-image. But the majority of her namesakes apparently didn't share this self-image. That was what worried her.

What she hadn't realised was how much a name says about a family's unconscious. Still less how significant it had been for her that her family - apparently unlike the families of the others - had articulated a reason for her being given the name she had.

To remain true to her own self-image she invented a mantra: 'You're not a worse person just because you have a common name, just like you're not a better person because you have an interesting name'.

The majority of the Linda Hansens she met were working class. That irritated her because what she wanted to prove was that nobody could conclude that a Linda Hansen came from a particular background or had certain limitations.

It was important for her to disprove the prejudices of the comment that had started the entire project. It became important for her that the women she photographed looked good. That they radiated charm and seemed positive and happy. And it became important for her that the viewer couldn't - on the basis of their apartments or houses - pigeonhole them. She wanted to make it impossible for people to think 'That's a typical Linda Hansen'. So she photographed them in totally anonymous surroundings.

But when she got home with the portraits the same questions emerged again and again: 'Why aren't we allowed to see anything other than the women? And why do they have to look happy?' She wasn't drop-dead gorgeous herself, so why did they have to be? When she got home and started going through the contact sheets she realised that the women she had photographed didn't look happy. That there must have been something else, something more important going on during their meetings that had overshadowed the happiness. Other moods and emotions than those she had set out to capture. That this was the case, and why this was the case, was something she first realised almost a year later.

Initially she tried unconsciously to hide her own shame at coming from a working-class family. How else could her attempts to remove her models from their surroundings be interpreted? She was trying to hide the physical evidence of their class. She was deluded into believing that class could be hidden. She believed in an ideal, and that's what she tried to isolate from all context. The project had become deeply personal. She was defending herself against prejudice. The coincidental 'common destiny' she shared with her models just made it difficult for her to see that this was the case.

III

Almost a year into the process she took a course that became a turning point. The photographers on the course were given the assignment of going onto the streets and photographing as an animal. She did a good job. At a time when she was reaching the limits of frustration over the results she'd achieved so far. The assignment made her want to explode - to use her entire body in her photography. To expose herself and stand by what she had created.

What the course made clear was why she, who thought she had resolved the issue of being called Linda Hansen, had spent almost a year taking picture postcards. She herself was prejudiced about her own name. Otherwise she wouldn't have been provoked enough to do the project in the first place. She'd always seen herself as a tolerant person who didn't judge others. But now she had to admit that she was biased too. She'd found herself thinking - when she arrived at the home of a new model - 'Jesus, this one's a typical Linda Hansen'. She'd been provoked again and again by prejudiced comments and opinions, but now had to face the fact that she herself had judged her namesakes. She'd betrayed both the coincidental common destiny she shared with the women and that she shared with her own family.

The realisation was painful but also productive. She visited each model again, changed style, and was more free and honest. She enjoyed uncovering the honest sides of herself and her models. Enjoyed going out to photograph a Linda Hansen and come home with her contact sheets to search for a true expression. To return to her models conscious of what she was looking for and follow through. She took the challenge of reaching her goal and photographing with her entire body. From her stomach, her heart and her sex. And it worked.

Almost three years later she'd reached the concluding phase of the project. She had developed a style. Discovered a language. And was starting to tell a story. The true story of Linda Hansen, the coincidental 'common destiny' and her own story - with everything that implied. The expressions were varied. She revealed information about each individual's environment. She continued to photograph new Linda Hansens, but focussed on taking supplementary photographs of those she had taken pictures of over the previous years. There were now 28 Linda Hansens in the project

Her biggest hurdle was her own self-portrait. Taking that photograph was a real battle. It was difficult because she - regardless of the realizations she'd had en route during the project - was just like everybody else when it came to her turn to be photographed. She wanted people to think well of her. That they should think she looked good - and nice. So she made a set of rules to avoid that. She decided that she would wear the clothes she'd had on all day. That she wasn't allowed to look in the mirror before she started shooting. She was to be subject to the same conditions as all the other Linda Hansens had been. She was satisfied with the self-portrait because it came so close to how she saw herself. The portrait was honest. Something she wasn't afraid to show.